Papers

Below we present papers we have written on the animations and Maya philosophy on time we have detected embedded in their art and worldview.

The duality of time, animation and the Bonampak murals

by Jennifer and Alex John

published 05/10/2020

Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me; but I am the fire

‘A New Refutation of Time’ by Jorge Luis Borge (1970:269).

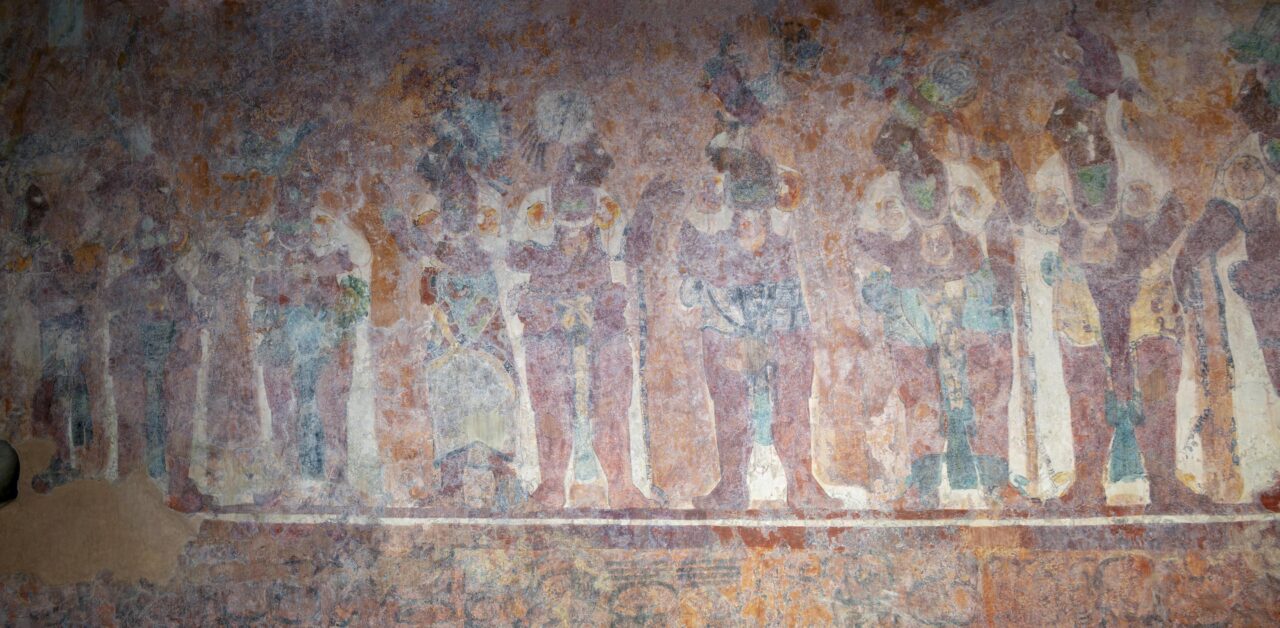

Mary Miller once wrote that ‘the greatness of Maya art could never be unravelled without addressing Bonampak’ and that ‘no study of the Maya could not treat the murals’, because without them it would be incomplete (Miller 2013:xiii-xiv). Accordingly, this paper represents an initial study of the animations at Bonampak and how they lead us one step closer towards understanding the story of the murals and the role of Maya art in general.

Since the rediscovery of the Late Classic Bonampak murals by American photographer Giles Healey in 1946, scholars have felt a desire to find a common thread running through the three rooms that house them; indeed, it was the subject of Mary Miller’s 1981 Yale dissertation. The search has been for a narrative uniting the three mural rooms – a single, overarching story with a clear beginning and end into which the complete storyline could be poured, much like the historical listings found on Maya stelae that tell of political alliances and battles, and the order in which they occurred (Miller 2013:xiv; Martin and Grube 2008).

Our new vantage point began after identifying a handful of animations in the Bonampak murals we presented in our book, The Maya Gods of Time (2018). Our new idea is that the Maya associated the number three with time. Furthermore, in the same way that the Maya associated the number four with space and colour (Seler 1902-03), we additionally contend that the Maya also associated the number three with wind and sound.

Miller and Brittenham (2013:20-21) draw attention to the ‘three-ness’ of the murals in The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court, Reflections on The Murals Of Bonampak, and also look at how it is used to frame Maya art in general. However, they do not link its conceptual use to time. Equipped with this new insight, we are given the opportunity to examine the Bonampak murals through a new lens, one that recognises the symbolic importance of their triadic composition linked to time.

It is not accidental that the murals encircle the interior walls of three rooms. In fact, the arrangement forms a deliberate symbolic structure alluding to the cyclicity of time, driven by the historical reoccurrence of birth, life and death, and supported by the dualistic frame the Maya saw time comprised of. It explains why scholars have encountered difficulties in imposing a linear-running narrative onto the murals. Instead, Maya recounts and stories merge the past, present and future; the past is the foundation for the present and the future is often an echo of the past.

We suggest the Bonampak mural triptych is ordered to a theme of temporal succession: in the east, a room is dedicated to cyclical beginnings, presided over by a god of the dawn, responsible for birth and creation in general. This is balanced by a room in the west, overseen by a god responsible for descent, demise, sacrifice and death, perceived as a type of sowing leading to cyclical rebirth. At the centre, in the largest room, a god of life presides, a god of ascending growth and balance. The roles of these three deities – cyclical birth, life and death – are the broad story that unites each of the three Bonampak rooms.

Once we accept that the Maya did not perceive time as being solely linear, and that the Bonampak narrative does not consist of a single thread, but rather of three interwoven rings moving from east to west, we may see how the painted figures orbiting the walls of each room complement each other, perpetually circumscribing them while advancing to the beat of time. Read in this manner – and following the path of the sun – the composition of the three Bonampak rooms reflects the three wheels making up the Maya cyclical calendar round, the ritual Tzolk’in and solar Haab counts, which interlock and turn together to place a dualistic frame on time, representing a moment (a given day) within the motional count of time. As such, the three wheels of the cyclical calendar round – and also the three Bonampak murals rooms – refer to the way in which time is ‘built’ in three parts. Here, the two smaller rooms exhibiting fewer figures become comparable to the two smaller wheels, while the larger central room displaying more ‘cogs’ (‘figures’) resembles the larger time wheel. The three elements form an allusion to our human perception of time in ‘three’, that is, as past, present and future.

The association of the three rooms with cyclical time is cemented into Room 2 by an eroded Calendar Round Date. The Calendar Round repeats every 52 years, a date that repeats rather than ‘being fixed in absolute time’ (Miller and Brittenham 2013:64-65). Its inclusion in central Room 2 supports the recurrent nature of the battle theme played out there. The Calendar Round cycle further linked the human condition to the cosmos: twenty ‘days’ relate to the human form exhibiting ten fingers and ten toes, the 260-day (20 by 13) Tzolk’in round is linked to ‘birth’, as it approximates the nine-month human gestation period, while the entire cycle (interlocking the 365 days of the solar Haab with the 260 days of the Tzolk’in counts) comes close to the 52-year life span of a human (see Rice 2007:30-39) – leading on to cyclical rebirth.

Returning to the murals, we can now compare the circular motion of the figures parading around its walls to the turning cogs of the wheels of time. However, the circular motion projected upon the mural artwork is not uniform. Occasionally, the sequential pacing of the mural halts, even turning against the overall flow of the murals. Miller and Brittenham (2013:21) noted how only the large deity heads in the room vaults are perfectly centred in their placement on their respective walls, while the remaining imagery beneath gives in to ‘gentle asymmetry’.

Accordingly, the actors’ performance replicates the way the world turns, like the imperfect motion of the clouds, stars, moon and sun in the sky, seemingly governed by the perfectly-aligned Gods of Time placed at the centre of the divine axis of turning time.

A deliberate visual ‘halting’ technique incorporated into the murals captures the viewer’s attention, the ‘hesitating’ figures standing out as we scan the murals, akin to the brief pausing of a movie or a camera shot lingering on a particularly poignant frame. As a result, the stasis of these figures is effectively juxtaposed with the turning movement flowing through the murals, to represent an instant, a perceived moment, contrasted with the flow of time.

This duality of time, juxtaposing stasis with movement, is also integral to the way the figural processions turn about all of the three room interiors, both clockwise and anticlockwise, relative to the central point of the room. Standing in the eastern and western rooms, the entering viewer faces the south wall. To their left (on the east wall), the figures turn clockwise, to their right (on the west wall), they turn anticlockwise. The oppositional pull possibly refers to how the two cogs of a wheel, when interlocked, move in different directions, one clockwise, the other anticlockwise. In combination, the wheels define a pincer movement that meets at the centre of the north and south walls. While the central Bonampak room subscribes to the same underlying momentum, a counter-current drives the mural imagery, consisting of swirling motion comparable to that of a frenzied hurricane achieved by overcrowding of the figures. Nevertheless, even in the metaphorical eye of the storm, the balance of the duality inherent to time holds true throughout the murals; it is the ‘idea’ behind the opposition and chiasmic structure that Miller and Brittenham first noticed in the murals.

Who-what-when is subordinate to rhetorical displays of parallelism, chiasmus, and other devices that emphasise similarity and cyclicity as much as historical difference

(Tedlock 1996:59-60).

Room 1 and 3 bracket Room 2 both literally and figuratively, creating a series of symmetries and alternations: dance-battle-dance; day-night-day; city-wilderness-city; order-chaos-order; perhaps also present-past-present. In poetry this kind of structure is known as a chiasmus, in Structure 1 as ABA’. It is a frequent device in Maya literature… and focuses attention on its central elements, granting them consequence and importance

(Miller and Brittenham [2013:68] quoting Christenson 2003:46-47).

This chiasmic structure frames Maya artistic compositions in the same way it frames texts (John 2018:282-283, 297-339). It has come to our attention that the central focal points of each room are often marked with animations. The animations highlight important moments of change, or transformation, comparable to the rising of the sun, the setting of the sun and the moment the ascending arc of the sun starts its descent.

Consequently, the murals reveal the duality placed by the Maya on time, where structure is balanced by change, time being conceived as both a moment and motion. This duality was deep-seated in Mesoamerican thought, present at the centre of the cosmic hearth that was set up during creation to ‘order change’ (see Freidel and Schele 1993:2), and forming the core of ancient Maya world view. We add that the three Maya stones of creation refer to the setting up of the duality of three-part time. The Maya stones of creation would be better named the stones of time as they refer to the creation of time when stone ‘time’ was framed by motional ‘time’ (see John 2018:61-70).

By extension, the unseen, which is invisible like wind, balances the seen, the visible. Equipped with this new insight into Maya philosophy, we can now return to the Bonampak murals. Here, the ‘unseen’ animation is framed by the figures that are ‘seen’. In this paper, we would like to draw attention to the great number of previously unrecognised animations, deliberated incorporated into the murals by their ancient creators. It is difficult to show the animations in a static publication, so we have included links that will spring them to life if you read an electronic version of this paper.

F1. Late Classic Bonampak Stela 2 showing Yajaw Chan Muwaahn II getting married (Bíró 2011); while the two highlighted ladies are named as different individuals, they complete a single action involving the raising of a bowl containing blootletting paraphernalia.

Obviously, the Maya did not have TV and movies, and so, in order to inject something greater than animacy into their artworks, they invented a visual convention intended to communicate the concept of animation. In literature these animations match a construct called a merismus, where two separate – and yet often related – devices frame an unseen central element to refer to a third, overarching concept. The literary device is frequently employed in the Popol Wuj texts. Christenson (2007:48) defines a merismus as ‘the expression of a broad concept by a pair of complementary elements which are narrower in meaning’. For example, in lines 64 to 65, ‘sky-earth’ represents creation as a whole, while in lines 338 to 339, ‘deer-birds’ describe all wild animals (ibid:48). Consequently, what initially appears to be a pair, is actually a triplet.

What is important is to read what lies between each pair or triplet figural depiction. This method of constructing something unseen from several ‘parts’ is well established in the Maya world; indeed, it is not unlike the way Maya scribes would build words from several phonetic and logographic parts. Once accepted, this visual convention opens up a whole new perspective on the Bonampak murals and Maya studies in general. It represents a step forward from the work of Søren Wichmann and Jesper Nielsen, who identified some ceramic animations in 2000. They also recognised the three-part frame, calling it A-B-C, but do not go on to connect this with time or transformation (2016:284; Nielson and Wichmann 2000). Our work opens up a world of metamorphosis linked to a deeply-rooted Maya philosophy centred on time as change. As we show on our website www.mayagodsoftime.com the same unseen dimension was also deliberately incorporated into monumental artworks across the Maya world, for example, at Quiriga, Copan, the Palenque Cross Group temples and in the Santa Rita murals.

We recognise that the animations we present form corruptions of their original artworks. However, similar to how rollout photography has served Maya studies for 40 years, our intention is to simply accustom contemporary viewers to this fresh way of seeing Maya art, with the purpose for them to then return, better equipped, to view the depth hidden within the original artwork when visiting Maya museums or sites.

The sheer number of animations we have found suggests that the Maya greatly appreciated their subtle ingenuity – visual plays, merismi, incorporated into their creations – much like the modern museum goer enjoys teasing the conceptual messages from twentieth century art. For example, when viewing Marchel Duchamp’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe!, the thrill lies in recognising the artist’s conceptual message communicating that the painting is not actually a pipe, but merely an image of a pipe.

The Maya visual convention was long-lived and widespread, reaching from Preclassic into Postclassic periods and throughout the Maya and Olmec regions. We can imagine ancient viewers scouring artworks in search of these visual puns expressed, for example, in the subtle shift of a musician’s hand playing a trumpet, a wounded warrior falling to the ground in a gradual state of undress, a powerful noble gesticulating to his court, or the elaborate dressing of a lord.

Our discussion of the Bonampak murals is structured in four parts:

- The three Bonampak lintels

2. The three Bonampak rooms and the metaphor of the day

3. The three Bonampak gods placed in the roof of each ‘house’:

The Maya Gods of Time

a. The eastern room: dawn, beginnings and creation

b. The western room: the end of days and sowing

c. The central room: life-is-a-battle metaphor

4. Conclusion

The three Bonampak lintels

A1. Details of Classic period Bonampak Lintels 1 to 3, carved and painted on their underside and supporting the three doorways leading into Structure 1 (see F1, left to right). To absorb the sum of the artwork the viewer must walk between the three lintels. Pieced together, the sequence animates the spearing of a captive grasped by his hair.

Pieced together, the Bonampak Lintel sequence (1 to 3) animates the spearing of a captive grasped by his hair. The lintels span each of the three doorways leading into Structure 1 and are carved on their undersides with imagery that requires the motion of the viewer, ducking between rooms, to trigger their animated content. Change between the first and second lintels is subtle, then greater in its jump from the second to third lintels. The different temporal spacing represents a specific pattern, a visual device frequently repeated in Maya animations to build anticipation. Initial change is slow, then sudden, like a watched pot seemingly never coming to the boil.

The Bonampak lintels reveal a broad Maya philosophy that unites their artworks and stone stelae triptychs with the human condition. The three different figures depicted on the lintels initially appear as one individual performing a single action: first, the figure is shown grasping the hair of a cowering victim (Lintel 1), followed by him dipping his spear (Lintel 2), before raising it again to impale the prone captive (Lintel 3). Viewing each of the three lintels requires a prostrate deportment, as only by lying back and looking up to see the image does the viewer physically assume the victim’s stance, shown dominated by the warrior above. Even though the lintel texts reveal the identity of the three warriors as different elite individuals separated by time (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:30, 65-68), they are united by their shared performance in a repeated event (i.e. the taking of a captive), which, although never recurring exactly, represents a repetitive human action. Despite each of the three lintels pertaining to a different protagonist in time (dated to January 12, AD 787 [Lintel 1], January 8, AD 787 [Lintel 2] and July 16, AD 748 [Lintel 3]; see Miller and Brittenham 2013:30, 65-68, table 1), the triptych movement flow shows a single temporal action linking a recurring historical event. Lintel 1 depicts the Bonampak ruler Yajaw Chan Muwaan capturing his victim in AD 787; Lintel 2 represents Shield Jaguar IV, the contemporary Yaxchilan ruler with his captive four days before the event described by the date on Lintel 1; and Lintel 3, it has been suggested, is probably Yajaw Chan Muwaan’s father killing his foe years earlier, in AD 748 (Miller and Brittenham 2013:65). Consequently, by recording repetitive events, the ancient Maya demonstrated a belief in the concept of cyclical reoccurrence (see Trompf 1979), where repeated behaviour echoing across time imposes a structure upon our lives and the surrounding world in which we live; and onto this structure the ancient Maya imposed a triadic configuration.

The lintels also comment on the interwoven politics of the two sites Bonampak and Yaxchilan, and the cyclical continuation or rebirth of the political line: the father in the west lintel is mirrored by his son depicted on the east lintel. As the father’s reign sets like the sun on the western lintel, his line is reenergised and he is reborn like the dawn sun through his son on the east lintel. Furthermore, the father-son pair frame the Yaxchilan ruler Shield Jaguar IV to form a politicaltriumvirate. The Maya believed that ‘governance in three’ provided stability of rule, in the same way that the three legs of a ceramic, or the three stones around a hearth, stabilise the bowl or cooking pot that rests atop (see John 2018:92). This triadic stability is balanced by the connected motion of a spear strike, where three players act as one.

As such, the repetition of important life and ritual events (e.g. birth, death, marriage or the ball game) and profane daily routines (e.g. the diurnal lighting of the three-stone hearth, maize grinding using a three-legged mano and metate, the motion of house sweeping or tending a milpa) creates an existential rhythm, whose content is played out by different persons over time and history (John 2018:99-100).

Similarly, the Maya structured their stories and the motion of their accounts, which were once ‘housed’ within their books, in ‘three’. The Popol Wuj creation account is recorded in the three tenses – past, present and future (see Tedlock 1996:63-74, 160-163, 221 [note 64]) – and the entire book is divided into three sections: including a description of the creation of the earth and its inhabitants, the story of the Hero Twins and their father and uncle and, finally, an account of the founding of the three K’iche’ dynasties (Christenson 2007; Tedlock 1996). The Maya also favoured triptych groupings of stelae, lintels and painted mural programmes. For example, the three lintels at Yaxchilan and the three painted Bonampak rooms ‘tell’ a tale. It seems that we compose a story from individual memories in the same way that threads are woven or counted to make a huipil by remembering these memories or patterns, respectively. In considering this we arrive at an often-revisited existential question, linking time to our own story (‘What is?’) and the deterministic thought surrounding the natural extent of fate (‘What is possible?’):

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos, or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted. But can those have been possible seeing that they never were? Or was that only possible seeing that they never were? Or was that only possible which came to pass? Weave, weaver of the wind. Tell us a story, sir

(Joyce 1986: Chapter 2/Lines 48-54).

At Bonampak, in order to absorb the entire mural sequence, the viewer is required to walk between three rooms, halting, to then pivot about their own axis within each room. Our own motion of viewing the three mural rooms links in with the paradox of time, each of us bringing a unique performance to the viewing of their images. Thus, our motion, subtle in its variation, is juxtaposed by the stability of the structure walls canvasing the murals, highlighting motion versus stability.

To this day, millions of visitors to Maya archaeological sites unwittingly perform the same performance and ritual walking linking circular time, ‘three’ and animation. For example, when visiting Chichen Itza and walking between the ‘rooms’ of the three famous structures – the Castillo, Ball Court and Temple of the Thousand Columns – to complete the tour, we may experience how each of these was subjected by the Maya to the structure of three-part time (see John 2018:111-221). As visitors to ancient sites, walking between the three Bonampak rooms, we therefore replicate the past motion of the ancient Maya, whose ritual footsteps we are now once again enabled to imagine because the symbolic significance of this motion is finally understood. Our motion is what activates and completes the artwork, as we, the viewer, become part of the duality of time.

The three Bonampak rooms and the metaphor of the day

The motion of walking between the three mural rooms, as is required from the viewer at Bonampak to activate the artwork, relates directly to an ancient Mesoamerican concept known as the metaphor of the day. Many Maya beliefs are centred on the common human experience of one ‘day’ – the unit that allows time and place, day and night, the sacred and profane, to converge (Earle 2000:72).

A person’s fate is compared to one day… death is like sun setting… [they would] implore the spirits not to cut their day short

(Earle 2000:100, authors’ parentheses).

A three-part rhythm structured day, year and life ‘time’ metaphors of the men who worked the fields, toiling beneath the sun. Earle (2000:80-81) records the movement of K’iche’ men walking from their home to the field and back again, returning to the cool of the house at noon, being tied to a three-part rhythm; the men’s agricultural chores, furthermore, changed throughout the year to match the seasons, in that they corresponded with, or were joined to, the changing motion of the sun in its relation to the horizon.

This process in the cosmos has its earthly counterpart in human activities. The wife wakes in the predawn chill and brings the hearth fire back to life from the coals of the previous night. The women begin to grind the kernels that have cooked all night on the grinding stones and slap the tortillas together, as the men rise with the sun. After a light breakfast, the men warm themselves and leave for the fields… and begin to work the land with their broad hoes… the men return home to eat the noon meal [Before returning to the field].

As the sun wanes in the afternoon… the men return home… men are like the sun… The adult man’s active role is one that follows a pattern of cyclical increase and decrease in heat as the day transpires. The women, on the other hand, remain predominately around the dark and unchanging house and canyon, insulated from the sun. Their work is constant, unchanging from day to day, season to season, regardless of the time they must keep the house swept, the water jar full, the children fed, and the food attended to. Thus, a complimentary opposition of male cyclical and female constant action is in the day cycle analogous to daytime and night or, alternatively, sun and earth

(Earle 2000:78-79, authors’ parentheses).

Walking between the three Bonampak mural rooms recreates this agricultural truth expressing the notion of something granted for something given. For something to live, something must die. The philosophy behind the metaphor of the day also sheds light on the dominant representation of men painted in the murals. The men are like the sun, they wax and wane with the day, while women are portrayed infrequently and within the ‘houses’ of the murals.

The few glimpses of the female world remind us that the court had another aspect, often hidden from view

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:84).

An explanation for the comparative lack of females represented in the murals may be that they represent the unchanging constant, the night or earth, seen as forming part of the metaphor of the day. Consequently, the overall symbolism of the murals most simply relates to the duality of time, the metaphor of the day providing a Maya explanation of the rhythm of life.

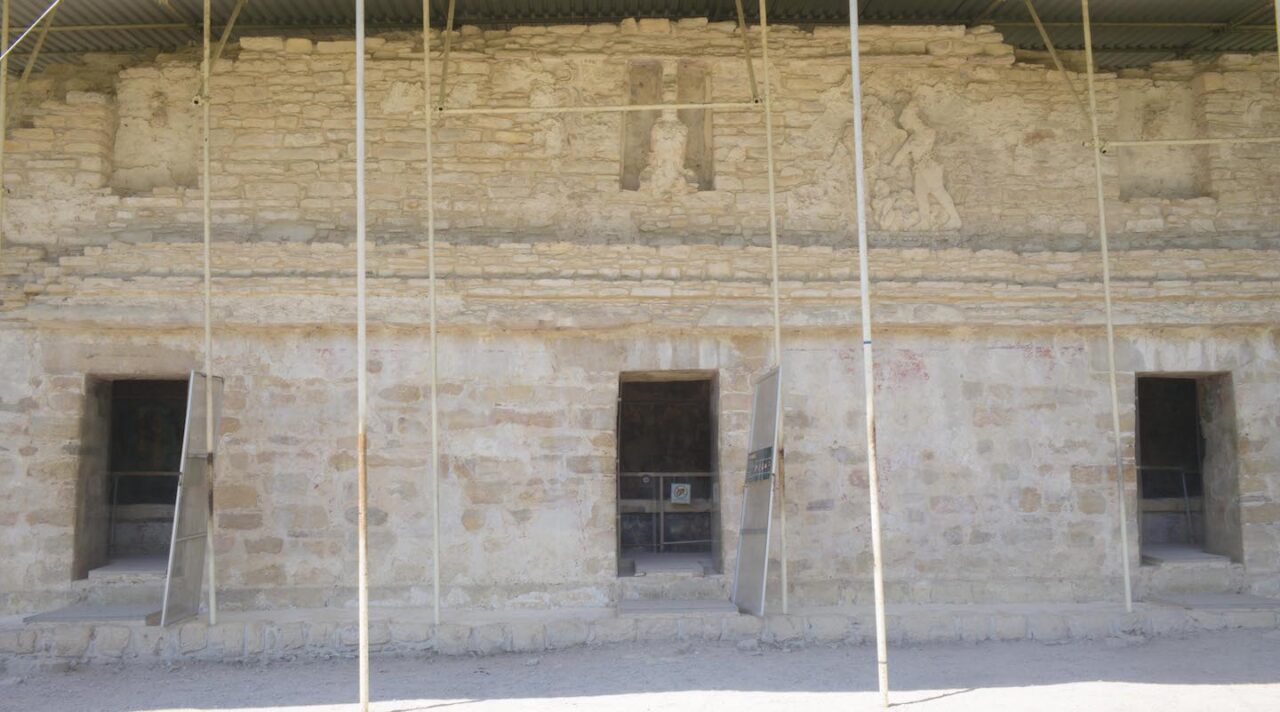

F2. Bonampak Structure 1 that houses the murals in its three rooms.

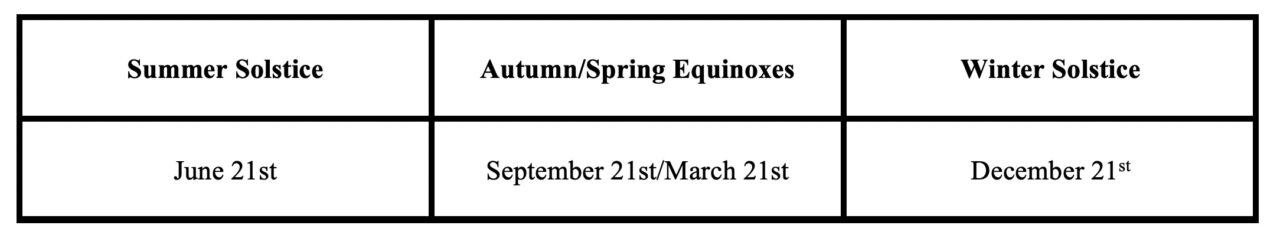

Since neither their Calendar Round nor the Long Count maintained consistent ties with the seasons, the Maya also devised a calendar linked to the sun, the Haab. They noticed that the sun passed or ‘interacted’ with the horizon in a recurrent seasonal troika.

… that curve which forms the golden swing in the sky.

(Calasso 1993:41)

The Haab created a rhythm which structurally connected the sun to the year through its movement in relation to three points: the autumn and spring equinoxes, which occur at the same ‘point’ in the middle, and the winter and summer solstices, placed at turning points either side.

Consequently, it appears that the Maya charted the movement of the sun in relation to the horizon. This interaction between the sun and the horizon was emphasised through the use of three points or ‘markers’, such as groups of three stone structures, to link three (stone structures) to time through the movement of the sun and the temporal rhythm of the year. Such giant stone structures occur, for example, at Uaxactun (Early Classic Group E), Caracol (A-Group, Structure 6; a large ahaw stone altar was placed at the viewing point atop western Structure A2), Calakmul (see Folan et al. 1995:315, fig. 4) and Tikal (Structure 5C-54, the ‘Lost World Pyramid’). Time was seen to move the sun between these three points and its three-part structure.

The triadicmovement of the sun in relation to the Maya solar year ties in with the politico-agricultural theme of maize running through the murals. Since antiquity, the longest day of the year has been celebrated across the world in association with the beginning of harvest and the turning point of the year towards darkness, while the winter solstice represents the opposite, with descent ending and renewed reascent beginning, linked to chthonic themes, sowing and resting. The solar rotation of ascension and degradation thus unites light and darkness. While the viewer moving between the Bonampak mural rooms now becomes comparable to the ‘golden swing in the sky’, moving like the sun between the seasons.

The three Bonampak gods decorating the roof of each ‘house’:

the Maya Gods of Time

We now turn to the trinity of gods that decorate the vaults of each of the three Bonampak rooms. If we accept that each of these rooms forms a miniature ‘house’, and that houses were used as miniature models of the world, then we can infer that the gods represented in their vaults are positioned in the sky, with themes of rain, thunder and lightning seeming most appropriate. We propose they represent a trinity of gods that each embody an aspect of the circle of time – birth, growth and death.

The idea of a trinity of gods is very ancient in Maya cosmology (Christenson 2007:71 [footnote 65]). A similar concept of religious triads also existed in multiple cultures across the ancient world. We believe the notion behind the trinity – associated with the cosmic hearth – is applicable to all Mesoamerican cultures, each exhibiting regional variants on their form, including, for example, the Teotihuacan Trinity (see Headrick 2007:104-11), the Palenque Triad (GI, GII, GIII) and the three Thunderbolt gods of the Popol Wuj.

Studying the animations hidden in ancient Maya artworks has led us to propose that this trinity of gods includes Chaahk (responsible for Sowing), Ux Yop Huun (for Life) and K’awiil (for Birth); they are comparable to the Hindu Trimurti Shiva (considered the Destroyer), Vishnu (the Preserver) and Brajma (the Creator), creating a conceptual link between ancient Asia and the Americas.

Thunder and lightning gods in other ancient cultures were perceived as powerful and omnipotent beings that could cause either death and destruction, or fertility and new life, such as Thor, Zeus and Indra. The conceptual origin of thunderstorms causing destruction leading to fertility is deeply entrenched in our human experience of nature, where violent thunderstorms precede spring rains that reawaken the divine life forces (Wilhelm 1950:298). This is also true in Mesoamerica, where thunder is linked to sound, and lightning itself was seen as a manifestation of powerful fertilising energy, as, for example, recorded in the myth of the origin of maize when lightning split open the rock containing the hidden seed (Freidel et al. 1993:139-140, 281).

The [three] stone hearths rend clouds of smoke redolent of wild anise, and the music of flutes brings thoughts of God

(Asturias 2011:49, authors’ parentheses).

Sound and music go hand-in-hand with religious ceremonies conducted throughout the world, the noise evoking primal emotions. While the sound described by the Guatemalan Nobel Laureate Asturias brings thoughts of gods, we suggest that the three Maya Gods of Time were linked to the noise of thunder, and were related to the three ‘Thunderbolt’ deities listed in the Popol Wuj creation account (see Christenson 2007:70-73 and Tedlock 1996:63-66); these time gods were, moreover, associated with sound:

First is Thunderbolt Huracan, second is Youngest Thunderbolt, and third is Sudden Thunderbolt. These three together are Heart of Sky. They came together with Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent. Together they conceived light and life

(in Christenson 2007:70).

Unlike other creation accounts, the above Popol Wuj passage does not appear at first glance to make a clear reference to the three-stone setting of time. However, closer inspection reveals the event encrypted within the text. The choice of words used to describe the birth of life reinforces the idea that the genesis of three-part time formed the vital moment of creation. We propose that the concept of time (including sound and stone) is incorporated within the three ‘Thunderbolt’ god names listed in the passage.

Similarly, we propose that ‘Thunderbolt’ forms a poetic reference to what separates and yet binds the two words; that is, thunder-lightning, which expresses the broader concept of time. As all the three Time Gods receive this title in the Popol Vuh, all three must therefore relate to the broader concept of time, while also suggesting a genetic relation.

The author of the Popol Wuj text chose to construct the word ‘thunder-bolt’ by combining the elements of two separate events. He juxtaposed the delayed sound of thunder rumbling with the flash of lightning. Consider how, when we see a flash of lightning, we instinctively begin to count. This reflex represents an ingrained anthropological trait enabling us to identify the centre and relative direction of storms to ensure our safety. Our suggestion is that the words chosen to form the ‘Thunderbolt’ title conceptualise the time elapsed between seeing a lightning bolt strike and hearing its delayed thunder, the clap. As explained above, this literary construct is called a merismus.

… There is also Heart of Sky, which is said to be the name of the God. Then came his word. Heart of Sky arrived here with Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent. They talked together then. They thought and they pondered. They reached an accord, bringing together their words and their thoughts. Then they gave birth, heartening one another. Beneath the light, they gave birth to humanity. Then they arranged for the germination and creation of the trees and the bushes, the germination of all life and creation, in the darkness and in the night, by Heart of Sky, who is called Huracan

(in Christenson 2007:70).

Heart of Sky, Huracan’s name, Christenson (2007:70 [footnote 62]) interprets as ‘the eye of the hurricane forming the divine axis around which time and creation revolve in endless repetitive cycles of birth and destruction’. The three Thunderbolt deities together form Heart of Sky, the Huracan of Time, a swirling axis of wind, lightning and thunder. The homophonous word huracán may refer to strong, swirling winds and the modern English word hurricane is likely derived from the Taino version of the word huracan (Christenson 2007:70 [footnote 62]).

The Thunderbolt deity we associate with K’awiil contains juraqan in his Mayan name. Juraqan translates as ‘one leg’ and raqan may refer to a lightning bolt or long flash of light. Christenson (2007:70 [footnote 62]) makes the association between ‘the one-legged god’ K’awiil (God II of the Palenque Triad, who was often depicted with one anthropomorphic foot and the other leg a serpent) and counting. ‘Leg’ may be used by the K’iche’ as a means of counting animate things, in the same way we refer to ‘head’ when counting cattle, and raqan to measuring out the length or height of an object (Christenson 2007:70 [footnote 62]). These associations provide evidence that K’awiil was linked to the count of time and measuring out.

We can imagine how measuring out would have formed an important part of creating a Maya artwork; whether on the curved surface of a ceramic, or a long mural wall, artists would have used cord and paper templates to create and space out the animations we have detected. We know that the murals were measured out upon the template of a grid (Miller and Brittenham 2013:13-20), with the motional tempo of the murals superimposed onto this structured frame of time. In this way, Maya artists mimicked the gods’ design of the time-space of the world.

A further element strengthening the association of the literary construct ‘Thunderbolt’ with ‘time’ may be found in the divination capacity of a Maya shaman. Known to this day as aj q’ij, they were regarded as having lightning in the blood (Christenson 2003:201) and were perceived as having the power to see beyond the limits of time and distance. As music frequently accompanied acts of divination (Looper 2009:58), it is possible that music and sound were also related to future-time.

In Mayan, ‘thunder’ translates as kilimbal chaak and lightning bolt as lelem cháak (Conde 2002:104 and 60). Furthermore, Mayan words for thunder and lightning bolt include references to the name of the deity Chaahk, here proposed as forming one of the three Time Gods.

We also propose that the deities’ names and connection refer to the associated time between the flash of lightning and the sound of thunder. Completing this circle of association, it seems that the connection the Maya saw between stone (as time) and sound carried great cultural complexity and depth. We found evidence of this association persisting to this day while travelling across the Yucatan peninsula at the end of the dry season. Staying in a small village near the archaeological site of Ek Balam, our meal was interrupted by the first great storm of the rainy season. Our Maya host began to count out aloud immediately after the first lightning flash, shouting ‘Chaahk’ as soon as she heard the thunder crack, all the while gesturing up to the sky. She was thus associating the count of time with sound and one of the Maya Gods of Time. The next morning revealed the destruction wrought by the storm, which would contrast with the future birth of crops ensured by its rain.

We have also found use of the thunder-lightning merismus as a reference to historical time in a dialogue recorded between Cortés and the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma:

It is true that I [Moctezuma] am a great king, and have inherited the riches of my ancestors, but the lies and non-sense you have heard of us are not true. You must take them as a joke, as I take the story of your thunders and lightnings [read times or histories]

(Díaz del Castillo 1963:224, authors’ parentheses).

Further evidence linking the Thunder-and-Lightning Gods to time may be found among the contemporary Maya. These Maya distinguish between vigorous and youthful lightning gods and gods of thunder, usually aged gods of the earth and mountains (Miller and Taube 1997:107). The same is true of the modern Huatec Maya of Northern Veracruz (ibid), which suggests a broadly established Mesoamerican perception of a temporal lapse existing between the flash of lightning (equated with youth) and thunder (as aged time).

Each of the three deities are included in a separate discussion of the three Bonampak rooms to demonstrate how their murals support the idea of cyclical beginnings in the east (relating to K’awiil), endings in the west (relating to Chaahk), with the largest and most central room connected to themes of life-fattening growth (relating to Ux Yop Huun): they are the three Time Gods.

The three Time Gods and their associated rooms are presented in the order corresponding to that of their manifestation during genesis, as recounted in the Popol Wuj and in other creation accounts (such as on the Vase of the Seven Gods and in the Santa Rita Murals; John 2918:188-195). They represent the three steps initiating, and then supporting, the never-ending flow of time, by propelling the sun along its cyclical solar path, which involved its birth, ascent (or growth) and descent in relation to the world; the three gods represent the gods of cyclical renewal, or more simply put, the Maya Gods of Time.

We have recently spent our time recreating the animations, presented below, ubiquitous in the Bonampak murals. The following sections approach the murals with the worldview of cyclical time, a philosophy that would have been widespread and known by Maya elite and commoners alike.

The eastern room:

dawn, beginnings and creation

Eastern Room 1 metaphorically expresses the theme of new beginnings, birth and dawn, overseen by K’awiil from the sky vault above. The large glyphs of the Initial Series text, painted in a wide band separating two figure rows, confirm the dedication of this room to ‘birth’ and the beginning of time. Miller and Brittenham write:

… if one given ‘reading order’… is preferred, it almost certainly begins with Room 1, which contains a lengthy Initial Series text, a genre of writing that signals the beginning of inscriptions on stelae, lintels, and other carved monuments… This reading order of left to right can be circular, if on a painted cylinder vase, but it is never endless; that is, it starts and stops, just as it does here

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:64)

A new perspective on the conceptual association of the Initial Series text and its surrounding imagery requires the recognition of the use of metaphor in Maya art. The start of the Initial Series text and the literal count of time is accompanied by the music of a band depicted on the east wall below, whose animated beat keeps time with the progression of the text; in fact, the image pairing forms an excellent example of the conceptual association the Maya placed between time and sound. Simply put, the beat of music created by the band depicted forms a visual metaphor for the count of time.

A2. Animation of a musician beating his turtle-shell drum with a deer antler. The beating and symbolic cracking of the turtle shell, symbolic of the split earth, with a deer antler probably forms a mnemonic to the bright dawn sun emerging as the large flaming fans painted immediately above. Deer were associated with the diurnal sun. Furthermore, the Maya maize god is frequently depicted emerging from the cracked shell of a turtle as sprouting new corn; the beating of the shell thus also announces the imminent arrival of the growth of new corn. Bonampak East Room 1 mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 51-53-55).

A3. Animation of parading musicians shaking rattles. HFs 60 and 61 are described in accompanying glyphic captions as k’ayoom or ‘singers’ (Miller and Brittenham 2013:81, fig. 146), possibly expressing ‘they begin to sing’. Bonampak East Room 1 mural details (HFs 57-61).

New importance is therefore injected into the measured ‘tempo’ with which the parading figures are spaced, the lower painted register of this eastern room now comparable to the steady beat of a drum, or the rhythmic shake of a rattle; at this ‘beginning’, time seemingly moves in a measured and predictable way. Furthermore, the temporal placing of the east and west wall figures conforms to an imperfect oppositional balance, a chiasmic composition (Miller and Brittenham 2013:68); consider how HF 72 (west) and HF 56 (east) simultaneously turn their bodies against the flow of the parade to indicate a change in speed experienced by the viewer as a pausing or halting. Likewise, Miller and Brittenham (2013:72) note how the parasols stretching up from the lower tier frame the Initial Series text on either side ‘like colourful quotation marks’. We propose that the shape and colour of the large fans represents a visual metaphor for the sun and its movement, over time, from east to west. The two eastern fan bearers are obscured from view, unlike their contralateral counterparts, who are animated to waft their fans up and down. Consequently, the animation that is ‘seen’ is balanced by what is ‘unseen’, fulfilling the duality of time discussed above. The breeze generated by the fans both starts and terminates the Initial Series text, thus forming a further reference to the association of wind and time.

A4. Motion of a large fan cooling dignitaries watching a royal dance and framing the Initial Series text that announces the beginning of time. The fan changes from orange to yellow; on the contralateral wall from yellow to orange. Bonampak East Room 1 details (HFs 73-74).

The visual reflection or chiasmic structuring present in the murals is similar to the literary ‘reflection’ found in the Popol Wuj creation account (Christenson 2007:46-52). Symbolic reflection in Maya art, like its literary equivalent, is inverted and imperfect, comparable, for example, to the way reflections in water are distorted. The deity Unen K’awiil, God of Birth and Dawn, is frequently marked with a mirror on his forehead to underscore his ‘creative reflection’ (John 2018:171-187).

The theme of beginnings also lends new-found meaning to the content of the Initial Series text, which has been suggested as mentioning an accession event, dated to AD 790, of a Bonampak ruler and which is recorded on Stela 1 as conducted in AD 776 ‘under the supervision of’ King Shield Jaguar of Yaxchilan (Miller and Brittenham 2013:64). The accession was planned to coincide with a total solar eclipse visible in the Maya region at the time (in AD July 790; ibid).

The Initial Series text also describes the erection of a god effigy associated with the east, the colour red forming part of its unusually-long Lunar Series text, and a house-dedication ceremony involving ‘fire-entering’, all timed after a solar eclipse (Miller and Brittenham 2013:71-72). Consequently, in addition to announcing the beginning of the count of time, the content of the Initial Series text also echoes themes surrounding new beginnings in the east: the erection or setting up of a deity linked to the east, the colour red, associated with the east, an accession, likely considered a form of being ‘born’ to the throne and the responsibilities this entailed, and the entering or starting of a new fire in a house-dedication ceremony – all timed with a total solar eclipse that was likely seen as a cyclically-returning rebirth of the sun. The text thus supports the idea that the eastern room was considered a ‘house of dawn’, overseen by K’awiil, the God of Dawn and Birth, whose forehead flare symbolised the fire or new light (lightning strike) entering the ‘house’.

Unlike the Initial Series text that moves from left to right – from the east to the south to the west walls – the parading figure rows beneath converge from the east and west walls on the south wall and the first scene encountered on entering the room [F3]. Here, three young nobles, ch’oks, literally meaning ‘sprouts’ (Houston 2009), are depicted dancing centre stage. Even though the three young dancers have been defaced, they originally undoubtedly formed an animation. The artists cleared ample space surrounding their performance, where the viewer may imagine their swirling steps accompanied by loud music. Each ch’ok depicted in Room 1 also wears a jade K’awiil-head diadem and jade jewellery rivalling that found in King K’inich Janaab Pakal’s tomb at Palenque (Miller and Brittenham 2013:3). The K’awiil diadems highlight the theme of birth tied to the dancers’ performance, while their jade jewellery was thought to aid rebirth and was frequently included in burials for this purpose.

F3. Three young nobles dancing centre stage beneath the wide band of the orange Initial Series text. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural detail (HFs 26-27-28).

The suggestion of the symbolism in Room 1 being tied to birth, regeneration and the theme of new beginnings is further reinforced by the portrayal of new maize throughout. For example, on the north wall the Young Maize God is painted sitting atop a turtle shell on the cylindrically shaped headdress of HF 42, who blows what is probably a whistle while shaking a rattle (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:118, fig. 224). Beside him, two trumpet players – also named ch’ok in the glyphs painted beside them (Miller and Brittenham 2013:79) – are animated to shift their hands as they start to play.

A5. A trumpet player shifts the position of his hands to start to play. Bonampak Eastern Room 1 mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:79, fig. 137 (HFs 43-44).

The sound of the band’s music is augmented by the percussive click and clatter of the claws forming part of a giant crustacean costume worn by HF 49 – a variety of shellfish mainly eaten at the start of the rainy season (Miller and Brittenham 2013:118-121). To the crustacean’s right, a further beast, HF 50, holds a possible drum and large beating stick or hollow wind instrument. The seemingly haphazard arrangement of these fantastical beasts, HFs 45-50, is unique in its depiction in the three mural rooms, the beasts’ masks indicating that they represent people performing a poignant moment within a play. At the centre of the scene, the Wind God can be seen handing a green maize cob to Unen K’awiil (NewbornThunderbolt). The exchanging of young green maize by the two deities – comparable to passing a relay baton – signals the moment when seed is gifted; it represents the instant of germination and reiterates the birth theme running throughout the eastern murals. A glyphic caption between the two deities reads baah tz’am or ‘head throne’ (Houston 2008), possibly referring to the Maya’s frequent equation of corn cobs with the head of the Maize God forming the fertile seed for future crops. Here, the moment of creation occurs at the spatial point where two opposing flows converge, as the meeting of opposites, where the two gods face each other, like night meeting day. The scene probably occurs before the ‘beginning’, signalled by the Initial Series text, as a kind of cacophonous prelude announcing dawn.

F4. The moment of creation, where two opposing flows converge and two deity impersonators face each other to exchange a corn cob, the seed for future germination and growth. Bonampak East Room 1 mural detail (HFs 45-46).

A6. Animation of the enactment of the possible transformation of a human into a crocodilian beast to mark the moment of creation signalled by the deity impersonators’ exchange of corn (standing immediately above, HFs 45-46), which represents the seed for future rebirth. The possible transformation is suggested by features of the first human actor (HF 47) carried over into that of the beast (HF 48), including the bulbous green collar edge repeated by the crocodile’s scales, waterlilies growing from their headdresses and the humanoid limbs of crocodile. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:79, fig. 137 (HFs 48-49).

A7. Animation of an elegant courtier turning to speak to the courtier behind him, who lowers his hands. Bonampak East Room 1, north wall, west-side animation. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:80, fig. 142 (HFs 75-76-77).

As noted by Miller and Brittenham (2013:53), the blue backdrop painted behind the dancers and musicians in Room 1 is a sparkling blue, created by layering coatings of Maya blue pigment with shimmering azurite. The east wall blue contrasts with a darker blue layering used as the backdrop for figures painted in Rooms 3 (and 2). The specific eastern blue achieved by overlaying shimmering minerals with colour was intended to capture the bright blue light of dawn, before the arrival of the warm colours of day. The same blue tone was also used as the backdrop for figures painted in the eastern dawn section of the Santa Rita murals, backing a representation of K’awiil in his role of the eastern God of Dawn (John 2018:298, fig. 5.1; F5). The dedicated use of bright and sparkling blue to refer to dawn light at Santa Rita shows the longevity of the conceptual use of colour, reaching into Postclassic times. At Santa Rita, and also Bonampak, as dawn progresses, the light quality changes, reflected on its east, south and west walls, and within its east, central, and west rooms, respectively.

F5.Late Postclassic Santa Rita mural reconstruction. The numbering (1-10) follows the general ‘rhythm’ of the two figure processions moving from the east and west towards the central door of the north wall. The figures are backed by sparkling blue in the east and pinkish red in the west.

In comparison to the other mural rooms, Bonampak Room 1 artists also used crisper calligraphic lines to outline figures and thicker pigments to fill in their shapes, resulting in brighter and clearer shapes of figures (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:56). The differentiation in painterly treatment of the figures in each room was intended to express dawn’s light once again filling easterly Room 1 and the world with bright new shapes and colours after emerging from the darkness of night.

Further evidence associating Room 1 symbolism with themes of beginnings is painted above the north wall actors performing the germination scene, where an important individual is shown three times to animate his robing. Dressing was considered a symbolic starting point in life, ritual and myth, representing a period when initial ‘nakedness’ was covered up (Miller and Brittenham 2013:127). The dressing scene is, therefore, easily comparable to the beginning of daily routines, the start of the day and the nudity accompanying birth. Placed immediately above the tier supporting the north wall actors, we are encouraged to also imagine the lord’s dressing as a performance, his undressing comparable to the husking of the maize cob exchanged by the two deities below and his own person thus becoming the seed enabling future growth and rebirth. The two scenes are linked by a narrower tier containing attendants seeing to the lord’s robbing needs and, in particular, by a green ‘umbilical’ cord [see F9] that is presented by a seated attendant to another holding up a large mirror that reflects the image of the cord up into the downcast vision line of the fully dressed lord.

A8. Animation of a lord dressing in three steps. Bonampak East Room 1, north wall mural details. Miller and Brittenham 2013:78, fig. 133 (HFs 23-25-27).

Another example of the East Room mural theme highlighting beginnings can be found in the depiction of a couple of ball players, who have been described as awaiting the start of a game, while standing alongside others waiting to perform (Miller and Brittenham 2013:121). Amongst these figures, HF 71 has, furthermore, just begun to smoke his cigar, obvious from its still intact length (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:122, fig. 232).

A9. Animation of a ball player turning while he awaits the start of a game. Bonampak East Room 1, south and east wall mural details. Miller and Brittenham 2013:80, fig. 142 (HFs 65-66).

In addition, an infant child (HF 16) is presented on the south wall opposite to nobles, sajals acting as regional governors (Miller and Brittenham 2013:121-122), while on the east wall, messengers, identified as such by their glyphic captions (e.g. yebeet chak ha’ ajaw, ‘he is the messenger of the Red or Great Water Lord’; Miller and Brittenham 2013:77, figs. 130-131), animate their delivery of new tidings with specific hand gestures; they gesticulate to announce the arrival of new information leading to new beginnings. The sajals all wear spondylus shells suspended in ‘three’ about their necks. Shells were considered skeletal flowers of the dead and symbolised the nocturnal aspect of the sun; the diurnal sun was symbolised by a blooming k’in’ flower (see John 2019:234-241). The sajals’ careful arrangement reveals hidden animations that give a glimpse into ancient high-societal hand gestures, their execution occurring in relation to the three shells they wear about their necks. Finally, the birth theme of the eastern mural room is further suggested by the radiating arrangement reflecting the sajals as a chiasm mirrored about its two central figures (HFs 8 and 9), who turn their back on each other to engage with the flow of figures converging on them from either side.

A10. Animation of messengers’ hand gestures. Bonampak East Room 1, east wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 1-2-3).

A11-12. Animations of messengers’ and high societal hand gestures. Bonampak East Room 1, east wall mural details. Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 4-5 and 6-7 [left to right]).

A13-14. Animation of high-societal hand gestures. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural details. Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 10-11 and 12-13 [left to right]).

F6. The two central dignitaries turn against the flow of the others to face each other; they stand back-to-back, forming the chiastic centre point reflecting the remaining dignitaries either side. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural detail.

A15. Animation of a high-societal hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, lower south wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 67-68-69).

The western room:

the end of days and sowing

The symbolism of westernmost Room 3 directly juxtaposes that displayed in eastern Room 1 of the same Bonampak structure. Room 3 is dedicated to sacrifice and death (Miller and Brittenham 2013:143) – which was seen as forming the oblatory ‘seed’ enabling future rebirth – and also represents a return to order. The preoccupation of Room 3 with death and sacrifice is contrasted with the theme of agricultural renewal represented by young (green) maize in the eastern Room 1 murals. Miller and Brittenham (2013:141) write that the anticipation of agricultural renewal presented in Room 1 was seen as brought on by the sacrifice and self-sacrifice of Room 3, the two rooms standing as a seasonal juxtaposition.

On entering the westerly room, ducking under Lintel 3 and looking up, we are reminded of the captive’s death, speared by Yajaw Chan Muwaan’s father [see A1]. A strong death theme continues into the interior of Room 3, which displays an opulent dance centred on a human sacrifice involving heart extraction (Miller and Brittenham 2013:34, 135, fig. 264). Straight ahead, the culmination of the dance is given centre stage on the south wall, where two attendants swing a body they hold by its arms and legs high into the air to form an arch – possibly straight after the removal of his heart, indicated by an attendant holding a small serpent-headed knife and the heart in its encasing white pericardium kneeling on the steps immediately above.

The blue tone of the sky painted behind the Room 3 figures standing atop the temple comes from a layering of blue pigment with both the minerals malachite and azurite, resulting in a darker sky than that used for Room 1 (Miller and Brittenham 2013:53). In contrast to the other two mural rooms, artists have also executed Room 3 figures using thinner, more watered-down pigments and little black paint to outline their shape, which emphasises their colour and the heaviness of their human form (ibid:56). The visual effect matches the fading colours our sight experiences at the end of the day. The great care taken in employing different artistic techniques to create visual effects, including the use of colour, form and substance, shows the importance the Maya placed on distinguishing, not just via symbolism, but also stylistically, between scenes expressing dawn in the east and evening in west.

Further sacrifice is represented in Room 3 on its upper eastern wall by a group of royal ladies who let their own blood about a spiked bowl containing bark paper (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:141, fig. 279). The ladies sit on a large throne letting blood from their mouths. The mural scene composition surrounding the women expresses a circular motion accentuated by the green edges of their white huipil dresses and necklaces, which combine to resemble a rope binding the motion of their performance. The viewer’s eye is initially drawn to the woman sitting on the floor before the throne, holding a small child in her lap. She faces away from an attendant kneeling opposite, who proffers bloodletting paraphernalia to the group. The woman turns to look up at a young girl sitting on the edge of the throne, who bends to rest her head on the back of a portly woman seated directly in front of her, herself intimately engaged with a smaller female she faces, who twists away from the last woman shown immersed in pulling the rope through her lips. All three women adopt the same hand gesture, binding their actions to the progression of time, further visualised by the three children seemingly growing from the infant held in the first lady’s lap, to young girl, to adolescent receiving initiation into the bloodletting rite.

The scene is similar to that of the enthroned lord shown seated high in the upper western wall section of Room 1, who, although not directly shown letting blood, sits on a throne beneath an oversized obsidian blade pointing down at him from the pincered jaws of an oversized deity head depicted in the vault above (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:125, fig. 235). The lord’s implied blood sacrifice balances the presentation of the new child depicted on the south wall of the same room. The lord sits surrounded by three women and an attendant standing to the left of the throne. Once again, a green ‘rope’ binds the scene to express temporal cyclicity leading to rebirth, flowing from the pictorial centre of the scene and the king’s neck and jade earrings and bracelets down to describing the edge of the throne, the women’s huipils edges and the edge of theattendant’s long skirt. As in the female blood-letting scene described in Room 3 (see above), the three women surrounding the lord in Room 1 appear of varying ages, possibly suggesting the lord’s same female family members. Indeed, some of their features, including hairstyles, match: the older woman sitting behind the lord in Room 1 partners the older woman seated on the throne at the far left; the younger female on the throne in front of the lord in Room 1 corresponds to the enthroned female sitting opposite (third from left); while the youngest female seated on the floor by the throne in Room 1 shows similarities to the youngest child depicted pressing her forehead against the enthroned woman’s back in Room 3. Once again, the choice in representing three women of different ages infers the circle of life inherent to ageing that is driven by time.

Both throne scenes, in Room 1 and 3, are notable for their lack of animations. Their omission is likely due to the rituals performed by the lord and ladies being culturally well-known to the Maya viewers, immediately aware of the content of movements conducted. The way they trigger knowledge of a conventionalised custom might be comparable to the modern representation of a traditional baptism, only requiring the presentation of an infant in a long dress beside a baptismal font to remind the modern viewer of the motions involved in the rite performed; that is, the priest wetting the child’s head with holy water.

The green ‘rope’ binding the performance of both throne scenes is repeated throughout the eastern room murals to refer to the cyclicity of time driving rebirth: for example, it also edges the long skirt and belt of the individual presenting the infant on the south wall, and is ceremoniously presented, via a mirror, by attendants depicted between the lord’s dressing and ‘grotesque’ actors performance scene and immediately above the door on the north wall leading into in Room 1 [see F10].

Returning to Room 3, we are reminded of death symbolism by the inclusion of skeletal centipedes emerging from the dancers’ back racks, a mnemonic for the venomous and carnivorous Scolopendra, common in tropical rainforests, whose foraging feeding habits accelerate decomposition leading to swifter renewal (Miller and Brittenham 2013:140-141). The depiction of dry (harvest) maize throughout the westerly murals also relates to sacrifice and offerings, the husks forming the seed for the sowing, necessary for germination and subsequent maize growth of the next season (ibid:141).

The dance depicted in Room 3 is performed by ten individuals, elaborately dressed in high quetzal-feather headdresses that support supernatural heads and ‘wings’ extending either side of their belts. The dancers’ elaborate quetzal feather headdresses would have cost the lives of many of these prized birds, who only produce two of these long tail feathers. The vast number of quetzal feathers serves as a metaphor for their great blood price. They also speak of the vast wealth of the court (Miller and Brittenham 2013:140). The dance unfolds across the nine temple steps surrounding the victim. It is restrained, the dancers encumbered by the elaborate costumes they wear. Many of the dancers also hold axes, reminiscent of Chaahk’s loud thunder, and fans, forming a mnemonic to wind. One dancer also wields a femur bone (Miller and Brittenham 2013:142).

Stone axes have been described as a symbol of lightning (Taube 1992:17); they are held by figures throughout the westerly mural and we suggest that they imply thunder, specifically the clap of thunder, while flint symbolises spent lightning. Stone axes are particularly linked to Chaahk, his loud thunder accompanying violent storms, terrifying, like death itself. Consequently, the stone axe probably formed a symbol of violence, used to chop and maim. Chaahk has been considered a god of rain and lightning (ibid); however, he might better be seen as a god of rain and thunder, often shown wielding the deity K’awiil like an axe, who, in turn, embodies lightning (John 2018:155-183). Creative acts and beginnings were possibly likened to lightning or the striking of fire, while thunder might have been equated with endings, metaphorically imagined as the sound of a flint axe splitting the sky. Such thunder axes, akin to Thor’s Norse Hammer or Damocles’ sword, were considered inevitable and final.

A16. Animation of the steps of a royal dancer. Bonampak West Room 3, west wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 27-28).

The winged loin cloth extensions of the dancers have been suggested as relating to auto-sacrificial bloodletting performed by their wearers, who also display sun attributes in their regalia (three of the dancers exhibit jaguar ears and pelts), all aimed at feeding the earth and Jaguar Sun of the Underworld, depicted high above in the north and south wall vaults (Miller and Brittenham 2013:136-141 and catalogue figs., pp. 216-225). The large sun heads in the vaults are mirrored across a red sky band to express the sun dyeing the sea red at sunset, evoking sacrifice. Furthermore, two jawless deities are belched from large serpent maws emerging either side of the large Night Sun heads; they are identified as the Patrons of Pax (Miller and Brittenham 2013:141), frequently also paired in ceramic scenes, where they receive sacrifices or hunt supernatural creatures (e.g. K1377, K9152).

A17. Animation of the steps of a royal dancer. Bonampak West Room 3, upper south wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 16 and 21).

A18. Animation of the steps of a royal dancer, seemingly alighting like a bird. Bonampak West Room 3, lower south wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 26-25).

The ‘winged’ dancers are accompanied by two bands, one consisting of individuals with deformed faces – suggested to be wearing masks exhibiting Olmec features to link the murals back in time (Miller and Brittenham 2013:142) – shaking rattles and beating a drum, depicted on the upper west wall, and one, four trumpets and one rattle player, represented in the lower tier of the north wall opposite the dancers. The ‘dwarf’-band musicians are far more numerous and tightly grouped, lending their music a more intense, or hasty, loud feeling. We can imagine the sound communicated by the mural imagery as music augmented by the stomping rhythm resounding from the dancers’ feet. Small ovals attached to ankle and calf bands suggest possible bells tinkling with every step taken. In addition, the long quetzal feathers of the dancers’ headdresses and large ‘wings’ would have swished through the air, along with their fans, as they performed their cumbersome dance.

A19. Animation of a musician blowing his long horn. Bonampak West Room 3, lower north wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:136, fig. 266 (HFs 46-47-49).

A20. Animation of a figure pair extending a baton or staff while striding forwards mirrored with that of another figure pair raising and lowering a flag. Appearing to rhyme, the animations form ‘book ends’ for the row of seven young ch’ok dancers performing on the lower steps of the temple depicted across the east-south-west walls of Room 3. Bonampak West Room 3, lower east and west wall mural details, respectively. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 11-12 and HFs 44-43).

In comparison to the overwhelming battle noise ‘discharged’ from central Room 2 (see below), chaotic cries of victory and pain, the westerly mural feels less ‘noisy’, or, at the very least, more ordered in its emission of sound, reflected by neatly-arranged figures parading as a visual chiasm. The change in noise in Room 3 is reflective of the still approach of the end of the day, death and the silence of night. It seems as if sound is winding down, slowing its pace toward a more civilised order, fully re-established in easterly Room 1 and its preoccupation with rebirth.

As was the case in the most easterly room, in Room 3 a row of nobles stands watching the dance, this time from beneath the Jaguar Sun Head peering down on them from the north vault. Once again, their arrangement forms a visual chiasm reflected about two central figures, HFs 55 and 56. Either side, these figures’ combined hand movements complete what probably form high-societal Maya gestures suited to the festive occasion. However, unlike in Room 1, the two figures forming the central reflection of the chiasm face each other, moving towards each other, comparable to the sun entering the sea in the west, as opposed to the sun leaving the sea at dawn in the east.

A21-22. Animations of standing dignitaries lifting and lowering their hands in a gesture accompanying animated speech. The hand gesture animations are arranged in relation to three spondylus shells, three ‘time’ stones, forming a mnemonic to the Maya hearth and creation. Bonampak West Room 3, upper north wall details. Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:143, fig. 282 (HFs 57-58 and 59-60 [left to right]).

A23. Animation of standing dignitaries lifting and lowering their hands in a gesture accompanying animated speech. Bonampak West Room 3, upper north wall details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:143, fig. 282 (HFs 52-53-54).

F7. These Bonampak figures’ hand gestures move about three shell ‘stones’ referring to the Maya hearth and the ordering of time during creation. Bonampak West Room 3, north wall mural details.

The central room:

life-is-a-battle metaphor

The largest and most central of the three Bonampak rooms, Room 2, depicts an elaborate battle across three of its walls (east, south and west; Room 2 also boasts the tallest bench [higher by 10 cm; Miller 1998:241-242]). The mural symbolism expresses the Maya belief that for one ruler to thrive, another must die. The room is overseen by Ux Yop Huun, the Maya Time God responsible for life’s ascent, growth and fattening; with the broad theme of the room communicating political ascent.

The sky above the battle scene on the south wall is a darker blue than that in the other rooms. The colour was achieved by the artists placing a thin layer of hematite red over a layer of Maya blue, creating a ‘visceral sense of time and place’ (Miller and Brittenham 2013:53). Indeed, the darker colour invokes thunderous clouds, and the hematite the red blood spilled in battle dyeing the atmosphere dark and ominous, while, simultaneously, feeding the earth and rain forest represented by a rich green backdrop behind the battling figures. The Maya frequently used red hematite to cover bodies and bones in burials (such as the Palenque Red Queen; see John 2018:163-164; Quintana et al. 2014); its inclusion in the mural pallet thus fittingly highlights themes surrounding spilled blood and death. In addition, Room 2 is the only mural room that revealed a subfloor crypt (Miller and Brittenham 2013:46), the hematite layer thus forming an elaborate funerary canopy covering the body.

The chaotically arranged battle scene contrasts with the ordered presentation of figure rows placed in neat tiers on its north wall (Miller and Brittenham 2013:105), a regularity which also represents the usual presentation of figures in mural Rooms 1 and 3. The three battle-scene walls of Room 2 feel alive, sprung with movement bursting out of their very edges. The chaos of the hand-to-hand combat conveys simultaneity and disorder, which Miller and Brittenham (2013:101-102) imagine as the least scripted and shortest part of Maya warfare – in contrast to regularised rituals marking the beginning and end of battles, such as music, banners and the eventual binding and stripping of captives. Writhing figures within the battle imagery convey the brutality and noise of war: battle cries seemingly swirl about the room like the driving gale of a hurricane. Many more figures are packed into the battle scene than appear in any other of the Bonampak murals. The increased head count suggests a loss of order, with figures overlapping, even blending together, ever-swelling towards a frenzied climax. The feverish motion pivots wildly around a point at the centre of the south wall:

And although the overall effect is chaotic, this chaos is carefully planned: warriors hold spears, and in any given section of the battle, the spears may seem to be aiming in random directions, but nevertheless converge just to the right of centre, on the lowest level, as if focusing attention on HFs 51 and 52

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:21).

The animations we have detected add urgency to the battle movements and their sound and further draw attention to important moments taking place within the mêlée. For example, a musician, or possibly a military trumpeter, spills across the south-east corner in a great arc to sound his trumpet. The long instrument is painted with crossed bones and eyeballs, while disembodied heads swing from about the trumpet player’s neck [A24]. Diagonally opposite, in the lower south-west corner, a warrior is shown collapsing to the floor and into the very centre ground of the south wall mural mentioned above [A25].

A24. Animation of a trumpet player sounding his instrument; his movements describe an arc reaching across the corner of the east and south mural walls in Room 2, like the sun ascending, then descending, in the sky (HFs 7 and 35).

A25. Animation of a warrior falling to the ground in a gradual state of undress to highlight his defeat. Bonampak Central Room 2, south wall mural details (HFs 64-58-52a).

Above the battle fray, a hieroglyphic caption records the lord Yajaw Chan Muwaan capturing a warrior; the text represents the longest and widest caption found in all three mural rooms (Miller and Brittenham 2013:68, 75), fitting with the overall ‘fat’ theme exhibited by Room 2. The ruler-warrior is shown grasping an opponent he has overwhelmed by the hair, his power mirrored in his jaguar headdress swelling in size to reflect his increased might and political stature [A26]. The artist has left an unusual amount of space around the ruler within the swirling mass of battling figures to allow the animation to play out and further draw attention to Yajaw Chan Muwaan’s performance.

F8. Progression of Yajaw Chan Muwaan shown grasping an overthrown captive by his long hair. Bonampak West Room 2, south wall details.

A26. At the point of capture, Yajaw Chan Muwaan violently jerks the victim by the hair. Simultaneously, his jaguar-head headdress swells to reflect his increased power. Bonampak Central Room 2, south wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:94, fig. 172 (HFs 54-55).

The battle scene is presented off centre; as you view the south wall mural the focus is off to the lower right and represents the ‘key and peak moment visually’ (Miller and Brittenham 2013:85, 98). The imbalance lends a dynamism to the scene which we believe was done intentionally in emulation of the anatomy and placement of the human heart within our bodies, which is also asymmetrical. The slightly skewed layout of the scene forms a simile to the beating heart – which sits off centre in the left of the thorax – of the battle, or, that of the deity depicted in the vault above, thus rendering the mural rooms comparable to the body of a god. The body consists of three parts: the head of the god is placed in the vault, the torso in the middle, where hand gestures dominate, and the legs in the lower registers, which show walking, dancing or the motion of battle. Ever-pulsating, ever-turning around the beating ‘heart’, the battle scene does not represent a single snapshot of the occasion, but rather expresses the constantly oscillating fight between defeat and victory – to reflect any and every battle, including that of life and death.

The measured hand gestures of the ten dignitaries depicted on the upper south and north walls of Room 1 and 3, respectively, frame and contrast with the frenzied hand movements of the warriors depicted in the battle scene of Room 2; the ten sajals, organised in two pairs of five, become comparable with the number of fingers found on a human’s hand, symbolic of counting and, by extension, time. Dismembered fingers have been found in Maya offerings (Chase and Chase 1998:308-309; Miller and Brittenham 2013:112), as are teeth, which change over the life span of a human; both fingers and teeth were likely linked to time.

Linear visual order seemingly returns to the central room on its north wall, comparable to a return to court from the field of battle, or the K’iche’ farmer returning home from the heat of the day. The king stands – like the sun risen high into the sky – atop the temple at the centre of his court and amongst displays of war spoils, ‘fattening’ gained from the battle depicted on the remaining three walls. The figures’ arrangement appears more spaced and choreographed to suit the sombre occasion; they do not walk, but stand to occasion, like a regimental guard. Subtle animations build suspense as figures wait on the king’s instructions. For example, to the king’s left, figures 95-96 exhibit a slight shift in the position of their left-hand fingers; to his right, figures 92-93 frame the motion of a torch or sceptre they lower [A27], while, above and below, figures 121-122 [A28], 115-116 [A29] and 111-112 change the positional grasp of hands on their spears, repeated also by figures 89-90 [A30], to the king’s right. The subtle movements hint at the anticipation, or ‘nervous’ fidgeting of the courtiers awaiting the king’s inevitable decision, petitioned by a captive cowering at his feet supplicating for mercy.

A27. Animation of dignitaries lowering their staff or torch. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:75, fig. 125 (HFs 92-93).

A28-30. Animations of dignitaries changing the position of their hands grasping their spears. The central animation also expresses the figures’ headdress swelling in size. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details. Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:75, 103, figs. 125, 190 (HFs 89-90, 115-116 and 121-122 [left to right]).